Sep 25, 2025

Week 1 - Among the Trees

Trees operate as integrated living infrastructures, shaped by biological process, spatial constraint and long-term stewardship.

Technical

Understanding trees as integrated biological systems of uptake, transport and structural stability.

This week introduced us to the field of arboriculture - the management and study of individual trees and woodlands as living systems embedded within human environments. Arboriculture operates at the meeting point between science, design and public life, ensuring trees remain healthy, safe and integral to community wellbeing. As we learned, a tree functions as a solar-powered fountain - a living organism sustained by the coordination of specialised parts.

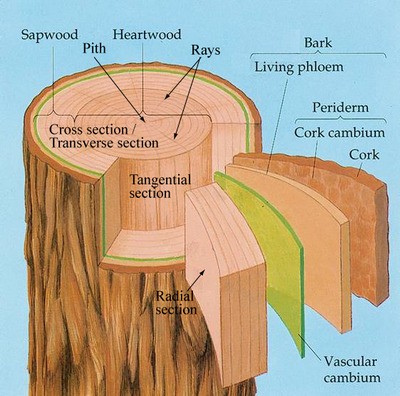

Roots serve as both anchor and engine, absorbing water and nutrients while storing carbohydrates for future growth. Root hairs increase the surface area for uptake, while mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic partnerships that enhance nutrient exchange. Above ground, the stem and trunk act as transport systems: xylem carries water and dissolved minerals upward, phloem transports sugars and hormones downward and the cambium produces new tissue, generating strength and renewal. Even the dead heartwood has purpose, providing durable structural support.

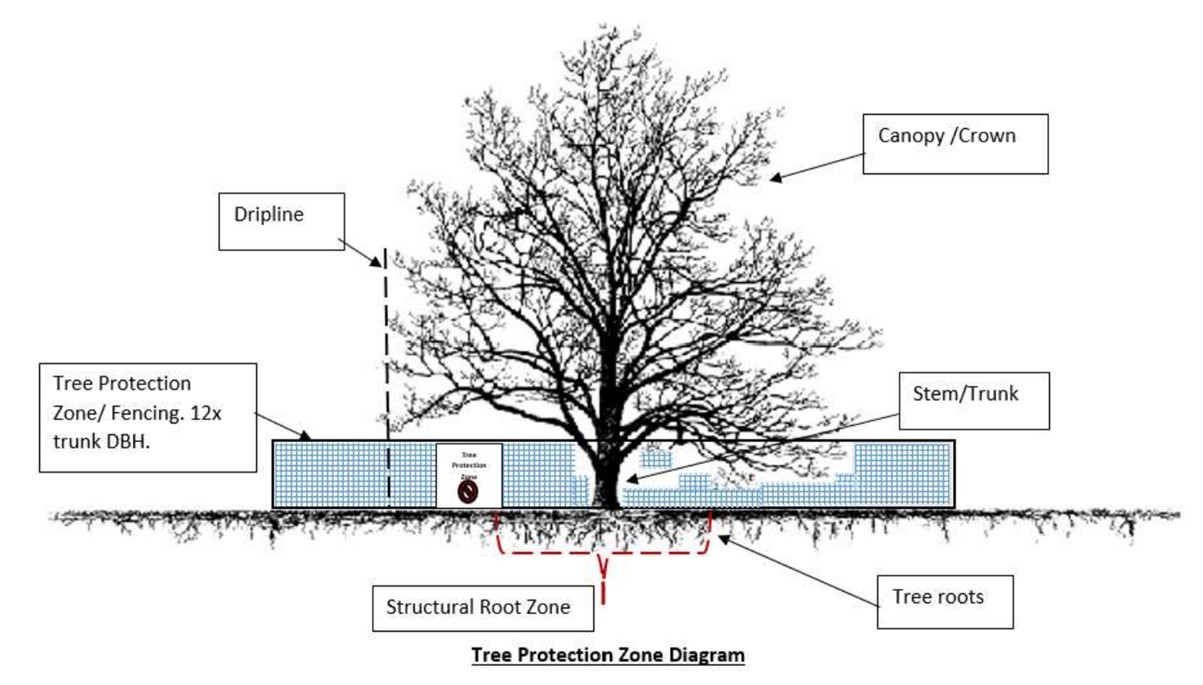

Our discussion extended to the Root Protection Area (RPA) - a critical design tool defined as a circle with a radius twelve times the tree’s stem diameter at 1.5 metres height. Devised by Dr Giles Biddle, the RPA safeguards the majority of a tree’s root system (found within the upper 600 mm of soil) from compaction and excavation during development. The principle is clear: beneath every design decision lies the duty to protect living foundations.

Arboriculture as a regulated practice balancing tree biology, risk management and development pressure.

The session emphasised that arboriculture operates within a complex human and regulatory context. Arboriculturists must translate biological understanding into clear, defensible recommendations for planners, designers, contractors and the public. We discussed statutory protections such as Tree Preservation Orders and the need for arboricultural reports to remain accurate, proportionate and confined to professional competence.

Central to this discussion was the Root Protection Area (RPA), a key design and planning tool developed by Dr Giles Biddle and formalised in British Standards. The RPA is calculated as a circle with a radius twelve times the tree’s stem diameter measured at 1.5 metres above ground level, representing the minimum area required to protect the majority of a tree’s rooting environment. Research shows that most fine roots responsible for water and nutrient uptake are located within the upper 600 mm of soil, making them highly vulnerable to compaction, excavation and changes in soil moisture.

Damage within the RPA, whether through heavy machinery, material storage or changes in ground levels, can lead to reduced oxygen availability, root death and long-term decline. The RPA therefore acts as a spatial constraint on design, influencing building footprints, service routes and hard landscape proposals. Arboriculture was framed here as a form of preventative engineering, where protecting soil structure and porosity is as critical as protecting the tree itself.

Tree selection was discussed using the Kew Gardens Tree Selection Guide, which prioritises ecological suitability over visual preference. Species choice must account for mature size, rooting behaviour, tolerance of compaction, waterlogging or drought, and potential conflicts with surrounding infrastructure. Shade and shadow analysis at midsummer was highlighted as a technical tool, as canopy form directly affects thermal comfort, daylight access and microclimatic conditions within public spaces.

Woodlands as layered ecological systems shaped by time, continuity and intervention.

The latter part of the session focused on woodland ecology, examining how groups of trees form vertically stratified systems that regulate light, moisture and temperature. A woodland is defined not simply by tree presence but by canopy density sufficient to influence conditions beneath, creating distinct layers: canopy, understory, field layer and ground layer. These layers interact to produce microclimates that support diverse plant, fungal and animal communities.

We examined ancient woodlands, defined in England as sites that have existed continuously since at least 1600 AD. Their value lies in ecological continuity rather than age alone. Undisturbed soils, long-established mycorrhizal networks and slow colonising plant species create systems that cannot be recreated within typical project timescales. Białowieża National Park was used as a case study of a primeval forest, illustrating both ecological complexity and the vulnerability of such systems to logging and political intervention.

Woodlands were framed as multifunctional landscapes providing carbon sequestration, air filtration, soil stabilisation and habitat, while also supporting timber production, education and recreation. From a landscape architecture perspective, intervention requires restraint. Effective woodland management involves surveying existing conditions, retaining deadwood, encouraging natural regeneration and designing access routes that minimise compaction and fragmentation. Practices such as coppicing, thinning and successional planting were discussed as adaptive management tools that maintain structural diversity and long-term resilience.

Reflection:

This session established trees and woodlands as technically complex living systems whose success within landscapes depends on informed stewardship rather than aesthetic control. Understanding arboriculture in terms of soil protection, physiological process and regulatory constraint highlighted how early design decisions directly influence long-term ecological health. For landscape practice, the lesson reinforced that protecting living systems below ground is foundational to any meaningful intervention above.